THE MOST CAPABLE SPORTBIKE BMW S1000R HP4

Just five years ago, the idea of BMW building a supersport literbike that could manhandle the class’s established players would’ve been a fanciful one. But that’s exactly what happened. It took class honors in our 2010 Literbike Shootout, and several subtle revisions for 2012 added up to significant improvements when we tested it at its launch in Valencia last fall.Less than one year later we’re back in Spain for the HP4’s launch, this time at the Circuito de Jerez, home of the Spanish Grand Prix. Never has a bike this fast been so easy to ride.

If the Japanese and Italian sportbike manufacturers weren’t yet quaking in their boots by the fabulously engineered S1000RR, the HP4 will surely make them fret. The standard S1000RR topped our rankings in our recent European Literbike Shootout, and the HP4 significantly ups the ante of what’s possible with a street-going superbike.

What’s In a Name?

The HP4 is the fourth model in the series of HP bikes kicked off in 2005 with the introduction of the HP2 Enduro, a high-end version of the R1200GS. The Boxer-powered HP2 line was later joined by the HP2 Megamoto, a supermotard version of the Enduro, and then came the roadracing-oriented HP2 Sport Pete rode in 2007. Consider the HP sub-series like BMW’s M automobile division.

To bring the S1000RR into HP territory, it’s fitted with a bevy of hardware and software upgrades. In the hardware section, aluminum wheels are now created by forging instead of casting, which results in lighter 7-spoke wheels. Together with a lighter sprocket carrier, the HP4 shaves a considerable 5.3 pounds of rotating mass. Also new are Brembo’s monobloc brake calipers replacing the RR’s two-piece binders.

The bike’s Race ABS and traction-control systems are newly optimized for racetrack use, and the ECU now has a launch-control function. The HP4’s rear tire is widened to the 200/55-17 size we first saw on Ducati’s incredible Panigale, and the RR’s optional GSA quickshifter is fitted as standard equipment.

The four-cylinder engine’s class-dominating peak power is unchanged, but a titanium Akropovic exhaust helps give it a welcome boost in midrange output and trims nearly 10 pounds of weight. The HP4 gets cosmetic enhancement with a racy blue-and-white paint scheme, a solo-seat configuration and a tinted windshield. A smaller and lighter 7-aH battery helps make the HP4 the lightest four-cylinder literbike, scaling in at 439 pounds with its fuel tank 90% full.

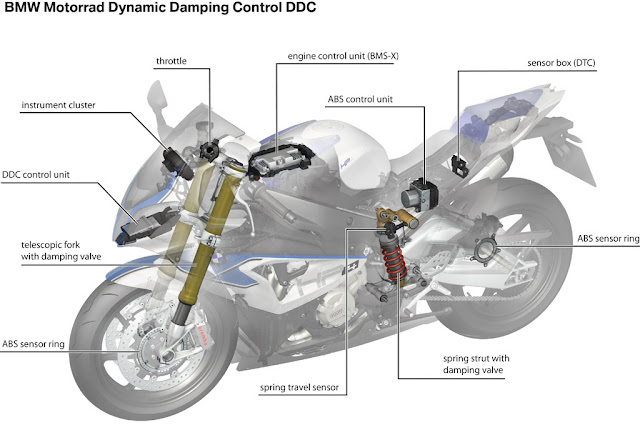

A World’s First – DDC

Headlining the upgrades to transform a RR into an HP4 is Dynamic Damping Control, a semi-active suspension system that automatically adjusts damping every 10 milliseconds based on how the bike is being ridden. The DDC’s control unit is mounted in the bike’s nose, and it’s fed data from wheel-speed sensors, throttle position, the shock’s travel position and the traction-control system, including its bank-angle data.

When set to one of the HP4’s street settings, Rain or Sport, DDC delivers a more compliant ride to absorb various road imperfections. Valving becomes tighter in the Race and Slick modes. Within each, the rebound and compression damping settings can be dialed up or down over 15 steps via the handlebar switchgear and updated instrumentation display. Spring preload adjustments require tools.

Because the system is “dynamic,” the electrically actuated suspension valves (first seen on BMW’s 1997 7-Series car) actively change their damping rates based on data pouring into the ECU. So, for example, while the damping is restricted for best control during racetrack use, the computer’s bank-angle sensor can inform the DDC to dial back damping when cornering at a deep lean when forces going through the suspension are less direct.

The right-side tube of the Sachs inverted fork carries the manually adjustable spring, while the left leg contains the damping circuits. Unlike the rear shock, the fork has no provisions for sending suspension-travel data. Optional from BMW is a fork travel sensor that hooks up to a provided input in the DDC computer. This allows for compression- and rebound-damping settings independent of each other.

The DDC performed flawlessly at Jerez, but it’s easy enough to get a good setup on a top-level sportbike for riding on a smooth GP track. DDC’s biggest benefit is likely to be felt on the street. To test the DDC in a street-ish environment, I noted the suspension behavior while riding Jerez’s bumpy pit lane. Then I shut off the ignition and observed harsher damping without the active damping in play.